Reviewed by Ryan Max

The great irony of international politics is how effortlessly it can destroy the people it is, in theory anyway, intended to protect. Lives are wrecked between all those press conferences and handshakes and in A British Subject, the multi-talented Nichola McAuliffe has written and acted in a gripping (and true) portrayal of one man's fight to stop the geopolitical gears from grinding yet another person into dust.

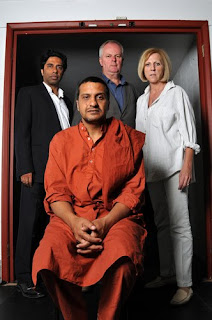

The man at risk of being lost here is Mirza Tahir Hussain, a dual British and Pakistani citizen. In 1988, the then 18 year old Hussain was jailed for killing a cab driver in self-defense while visiting family in Pakistan. By the time any Western press outlets notice Hussain's plight, he has been on death row for 18 years. Don Mackay, a journalist for England's The Daily Mirror (and husband of McAuliffe), flies to Pakistan out of professional obligation but becomes obesessed with telling Hussain's story and winning his freedom.

Maybe it's a given that Don Mackay would be painted as a sympathetic character, seeing as his wife wrote the play, but Tom Cotcher's portrayal still works perfectly to get the audience behind his quest to free Hussain from prison. He is easily identifiable for a Western audience as a stand in for the average apathetic observer: glib, sarcastic, and numb to the horror stories that flood the media.

It is only when he meets Hussain face to face, in the play's riveting centerpiece, that Mackay's feelings shift. After he artfully gains access to interview Hussain--the first journalist to even attempt the feat in his 18 years on death row--Kulvinder Ghir, the actor who plays Hussain, gives a performance of languid motions and whispers that cut straight to Mackay's heart.

What allows the play to be engrossing, funny, and heartbreaking all at once is the near-perfect production. Lighting and sound are crafted for maximum effect, but restrained enough to skitter on the edge of melodrama without surrendering to it. A striated square of harsh light with a background of faintly buzzing flies transports the audience seamlessly from, say, the stuffy British ministry offices to Hussain's Pakistani prison cell.

In Hussain’s cell, the background sounds of traffic and honking that washed over the stage when Mackay was outside on the street fade, and the low buzzing of flies in the prison slowly gives way to a crushing silence. Hussain's words are so soft and slow, and the absence of any other sound so striking, that the audience becomes painfully aware of its own noise. Coughs and wheezes (it's winter in New York) become deafening as Hussain details the horrors of his life in prison. The effective restraint in tech and performance also extends to the dialogue: Hussain doesn't speak in easy prison cliches such as the stench, or beatings, or boredom. Instead, he explains how they can't even play chess anymore, because "with nothing else to do, people cannot bear to lose."

The second half of the play, dominated by Mackay's passionate campaign to publicize Hussain's plight, struggles to match the first half's breathless pace and palpable tension. At times it does, like when Mackay's wife (a role which has McAuliffe playing herself) shouts at someone explaining that “at least” Hussain’s execution isn’t until New Year's Eve: "While you're singing Auld Lang Syne, he'll be evacuating his bowels at the end of a rope."

That the play fails to wring any real drama out of the quest to free Hussain can be partially attributed to the facts of the story: the efforts took place mostly in Britain, mostly between people who weren’t in as desperate (or interesting) situations as Hussain himself. Transitions between scenes may still be seamless, but the locations to which they transport the audience are hardly worth visiting. Absent the tension of the first half, focus is drawn to the play's weaker themes, such as the relative merits of faith and reason, prayer and action as a means to spring Hussain. When these limp themes take center stage, it’s akin to the background sounds becoming the main dialogue, and it’s an odd position that the second half puts you in: wishing you were back in prison with Hussain.

-------------------------------------------

A British Subject (75 minutes; no intermission)

59E59 Theaters (59 East 59th Street)

TICKETS: $35

PERFORMANCES (through Jan. 3; no performances Jan 1): Tue 7:15, Wed-Fri 8:15 (except 12/31 @ 7:15), Sat 2:15 & 8:15, Sun 3:15 & 7:15