Absurdity is a good thing, but when the device trumps the message, it's gone too far. Mark Lindberg's Truce on Uranus has some fun with the writer-in-a-play conceit, but without characters to interact with, it's a one-author show.----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Reviewed by

Aaron Riccio

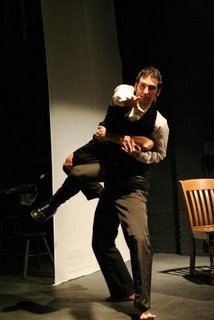

Photo Credit: Frank Kuzler

Mark Lindberg has written himself into a tough spot: he's trapped on Uranus, a planet so cold that it's "too cold to live" and "too cold to feel cold," admitted that he's written himself into a corner, and been subdued by an ambivalent transexual alien who goes by the name Titania (the vocally gifted David A. Ellis). Lucky for Mark, he's only directing and writing

Truce on Uranus, even luckier, the actor who plays Mark, Ricardo Perez Gonzalez, has charisma-and-a-half: that natural theatrical grace that makes us want to follow him across the stage, even when the stage, script, and underlying emotions are threadbare. When "Mark" complains to the audience about how difficult it is to write a play or to be in The Theater, it's compelling and believable. This is grounded in the artist's fundamental truth, even if the show itself, set on Uranus, is not.

That's the real kicker--whereas Edward Albee introduced fantastical lizardmen in

Seascape to deliver a message about social acceptance, Mark Lindberg doesn't go far enough with his frigid landscape. Escapism's a fine theme, but from what? A fight with his boyfriend, Desi? If Mark needs to construct this much metadrama to reconcile his love, the play should reflect that. Instead, there are passionate monologues coupled with bland and ambiguous scenes, a pairing that so imbalances the show that the individual shifts between comedy and drama go unnoticed.

The problem--and this stems back to putting oneself into the play--is that everything's intellectual: Lindberg loses the message to the device. There are clever twists, like the way Lindberg overlaps scenes (characters in the background freeze as the material they're reading is recreated in the foreground), but then there's also Cassandra, a character within a play within a play who--oh yeah--also happens to be dead. Men have done sillier things for love, but was it really necessary (as Mark-within-the-play puts it) to obfuscate so much?

The concept shows promise, and Hannah Davis's lush, trippy set design (purple and yellow paper-mache mountains) gives the show a vibrant playland to live on. But the palette is mostly underused, and by the end of the show, it seems that Lindberg is simply flinging himself at the same few jokes, over and over again.

It takes more than keen excitement toward the ridiculous (see the curtain call), to build a show. But

Truce on Uranus tries so hard for the big picture--"You'll just have to read the play and when you figure out what it all means, let me know"--that it misses out on character. Coupled with nerves, missed technical cues, and/or lazy direction, the dialogue starts to fill with yawning chasms of dead air and the lack of chemistry causes an emotional detachment that undermines the need for escapism.

We all need to escape; but theater has to bring us back, too. And until Lindberg reins in the absurdity long enough to establish character,

Truce on Uranus is going to stay out of orbit.

-----------------------------------------------------

Dreamscape Theater (www.dreamscapetheater.org)

Hudson Guild Theater (

441 W 26th Street)

Tickets (www.smarttix.com): $15.00

10/13 @ 8; 10/14 @ 1; 10/18, 10/20, 10/24, 10/28 @ 8:00